On Friday, May 7, 2021 I received an important email.

The email began with “Dear Masha Shukovich” and proceeded to inform me that I am on the longlist for the 2021 First Pages Prize, which supports emerging, unagented writers worldwide with an annual prize for the first 5 pages of a longer work of fiction or creative non-fiction. This year’s judge is Lan Samantha Chang, the Elizabeth M. Stanley Professor in the Arts at the University of Iowa and the Director of leading American MFA program, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

The email read:

“With a dazzling array of themes and genres represented this year, and over 2,000 entries received from 54 countries, our judging committee were hard-pressed to select these 36 longlisted entries. The quality of writing across the board was very impressive and a great number came close. Congratulations to all.”

I kept rereading the email, starting with my own, correctly spelled, name. It felt like an out-of-body experience: disbelief, joy, tears, all commingled. I was ethereal, floating.

I kept thinking: “This can’t be right. They must have made a mistake. English isn’t even my first language.” But no mistake was made; it is really my name, my work, on that list filled with magic and wanting and always more hope for something even greater.

My imposter syndrome is a living, breathing, starving beast with a nearly impenetrable hide. It doesn’t matter how many accolades it receives, how many writing awards I feed it, how much praise comes its way. It remains ravenous. My wound of not belonging, of being “the thing out of place,” an error in an otherwise error-free reality, goes way deeper than my 17 years in the US.

But it matured and earned its name here, much like me.

It’s happened many times since I came to the US from the “dark” Balkans as an international student back in 2004:

I meet a new person and they cock their head to one side, narrow their eyes and ask:

“Where are you from?”

It used to enrage me. My brain would instantly translate it into: “You are not one of us. You don’t belong here.”

The asker of the question may think they’re expressing their curiosity or interest. But it doesn’t feel that way in my body. It feels like hostility. It feels like danger. It feels alienating. And it feels unnecessarily cruel, to point a finger at my wound like that and then stick it in for good measure. But the cruelest, most alienating thing of all is that I know that the askers of the dreaded question are right.

When I open my mouth to speak, the discomfort intensifies. Sometimes cashiers will talk to me very slowly and deliberately, to make sure I understand. Once a very irate TSA worker (older, white, male) told me that I look like I speak Spanish (I do speak Spanish. I don’t know about looking like I do). Sometimes people take one look at me and ask: “Do you speak English?” I guess to some people I look like I don’t.

But the truth is, I do speak English. I even dare to write in it: poems, stories, articles, blog posts, and now a book. I even dream in it.

I taught myself English (not grammar, which was already taught at my elementary school in endless lists of irregular verbs and definite/indefinite article rules, but the soul of the language) by watching the reruns of Cheers in my parents’ high ceilinged postwar apartment. There was a giant, concave indentation in the yard we shared with our neighbors, where a WW2 bomb once hit the ground, leaving a cracked footprint for all to remember and never forget. The bomb never detonated. And we did forget.

But there was one thing that defied all forgetting: the voice, which seemed to come from a place vaster and more forgiving than my human skin, that was as old as my 11-year-old consciousness; perhaps even older, predating the life as I knew it. It would sometimes whisper, sometimes scream, at times even plead, but it always said the same thing: learn all you can.

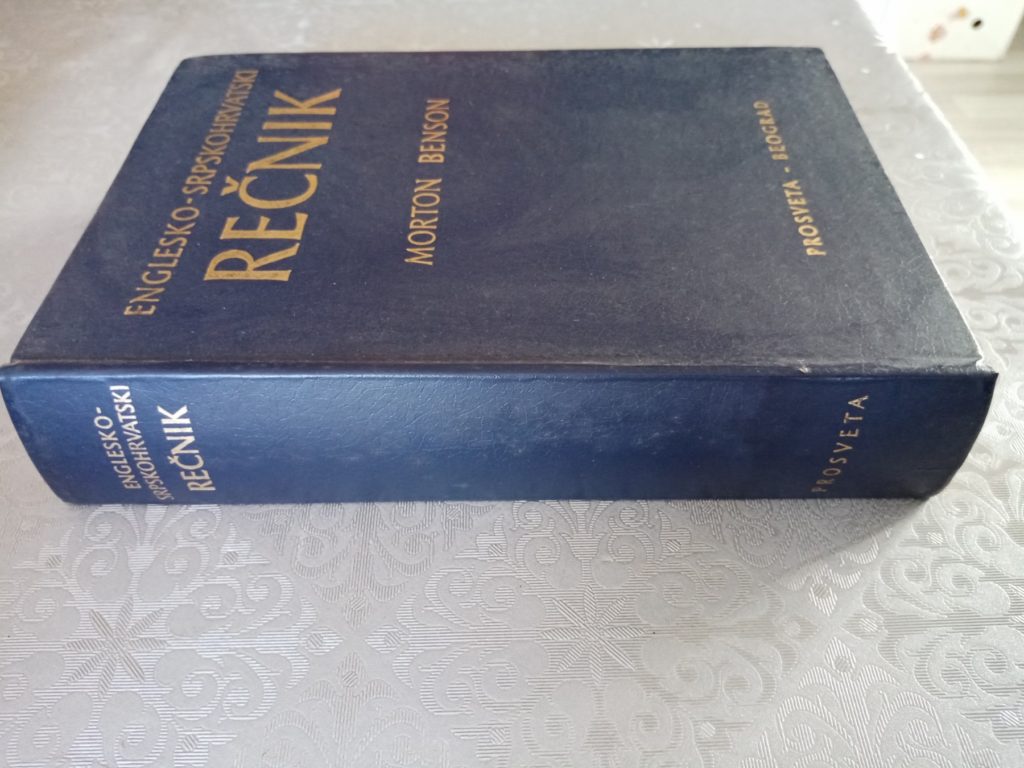

So I sat with my heavy “Morton Benson English-to-Serbian Dictionary” (it was navy blue and smelled like new shoes) in front of the convex TV as old as me, watched Diane scream at Sam, Carla scream at everyone, and Norm wrap his thick roots around that corner barstool. And I learned all I could.

One of the phrases that school didn’t teach me, but Cheers did, was “eager beaver.”

It was a source of great mystery to me. There was no Google search, no internet even, back then. It existed, of course, but we were too poor and insignificant to “have” it, even the slow and noisy dial-up kind. That came a few years later.

There was no one to ask, and even if there were, I wouldn’t have dared, for fear of being forced to explain why I was doing this crazy thing: watching an American comedy show, audio-taping it, and taking extensive notes of words and phrases to look up later. I had no answer to that, beyond the fact that every cell in my body wanted to grasp this foreign language and hold it long enough to really know it. It was like being in unrequited love. Sickening. Beautiful. Impossible to stop.

I was full of questions and terrified of asking. The burden and joy of finding the answers was all mine.

In the absence of other options, I ruffled frantically through the “Morton Benson,” hungry to know. The dictionary had a cold, repressed energy about it; it would not yield itself to this undignified scrutiny.

It had “beaver” and “eager,” sure, but “eager beaver” wasn’t there. I started thinking I misheard it, made it all up. But I was anything if not prepared: I had my trusty cassette player by my side, the same one I used on our crumbling balcony to listen to the 60s US rock: the music of my parents’ youth that I was dying to claim as mine. I couldn’t videotape the episodes, so I would obsessively audiotape them, for further research. I rewound the tape and pressed play. And there it was, delivered in Carla’s shrill, nasal voice: “You are such an eager beaver, Cliff!”

My brain went into one of its many overloads, the one I also know as the “must.solve.mistery.now mode.” But where could I possibly look? In desperation, I reached for my shabby but infinitely more friendly pocket dictionary. The pages were so thin, you could see the outline of your own hand through them. I took a deep breath and dived in. And there, right in the middle of the page, cocooned like a caterpillar, was the eager beaver, waiting for me to find it.

I don’t have that little dictionary any more, although I still feel its tiny heart beating, somewhere. I can’t tell you what the entry said, but I suspect it went something like this: “a keen and enthusiastic person, somewhat naive, who works very hard.”

A great relief came over me, if only for a moment: I had found my answer. I knew something. It felt like that moment when you’re washing dishes and your nose starts to itch, and after an endless minute of agony you finally dry your hands on a towel and blissfully scratch your nose. It felt that good.

I now see (probably because it’s SO on the nose) that I was really looking for a way to define me. I am still that eager beaver. I still can’t resist a good question and answers are life. That is why I write.

And now, I am in utter disbelief that this kid, who audiotaped old episodes of Cheers and picked at them like a velociraptor until they yielded the meat of their answers, this kid who taught herself ‘”American” with a hearty combo of mania and a pocket English dictionary, would grow up to become a fairly well-adjusted adult who still finds answers by sifting through words and laying them down on the page, all in a language vastly different than any of those spoken by her ancestors.

I am one of the 36 longlisted writers who sound like they might have answers. Maybe we do. And maybe we’re still out there, digging, searching. Some of us may eventually give up. Some of us will search until we draw our last breath. It all depends on how hard the questions are and how much we want the answers.

And to that overly enthusiastic, buck-toothed 11-year-old self in Yugoslavia, the country that no longer exists, I say, every time I plop myself at my writing table, exhausted from my life but still as eager as all hell:

“Not much has changed. You still need a dictionary. But let’s write anyway. ”